JAPANESE LACQUERWARE has long fascinated the West. When Christian missionaries first came across urushi lacquerware in Japan during the 16th century, they were so impressed with it, they brought pieces back to Europe and called the unique products “Japan.” Centuries later, more than 70 pieces were discovered in churches and monasteries in Spain.

In the 18th century, urushi products were in vogue among European royalty and the artistocratic class. Maria Theresa dedicated a whole room in her palace to Japanese lacquerware. It’s said she loved those products more than her diamonds.

Europeans tried to copy the look in a process known as “japaning,” where flax oil or copper oil was combined with black powder. Through trial and error, European artisans improved their lacquer, but the resulting look was no match for the deep black of urushi.

In those days, the pianos were wood-grain, but the companies started japaning them, which is why today’s pianos are jet black. That’s right, the color of pianos can be tied back to an aspiration for Japanese lacquer!

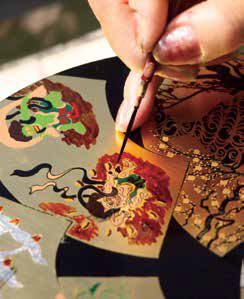

One of the things that makes Japanese lacquer so beautiful is the maki-e technique, which was developed in Japan in the 8th century. Craftsmen would paint patterns on a plate or box with urushi lacquer, then sprinkle gold or silver powder over it.

This phoenix display plate uses a technique called takamaki-e, or raised maki-e, which requires the highest standards of craftsmanship. The result is a phoenix, said to bring prosperity, that has three-dimensional depth to it.

Yamada Heiando went into business in 1919 and has been supplying lacquerware to the Imperial Household in Japan ever since.