Spreading Sunshine through Comedy

Spreading Sunshine through Comedy

From ORIGAMI magazine

The first Westerner since Japan’s Meiji Era to become an accredited rakugo storyteller is ready to crack you up

Rakugo, sometimes referred to as “sit-down comedy,” is a traditional form of storytelling where a comedian uses a couple of props – chopsticks and a towel, typically – and, staying seated the whole time, tells the audience a story. Often the stories date back hundreds of years. A rakugo master will perform all the characters in the story, spinning yarns that range from amusing to side-splitting.

This ancient storytelling tradition may be the most difficult realm of Japanese culture for a foreigner to enter. Strict apprenticeships last three years and involve a lot of menial labor ―hours and hours of laundry, dusting, and kimono folding, for example. Plus, the Western acolyte has to figure out how to tell comical stories in Japanese. No wonder, then, that there hadn’t been a Western rakugo-ka, as the official storytellers are called, in more than a hundred years until Katsura Sunshine, a successful playwright from Toronto who fell hard in love with rakugo on a visit to Japan more than 20 years ago, became the first. Sunshine even had a successful off-Broadway run that was cut short by the Covid-19 pandemic. His performances received rave reviews by The New Tork Times, New Yorker magazine, and others.

We checked in with Katsura Sunshine in Tokyo recently to talk about his upcoming virtual performance on October 20th (see the sidebar for details) and find out how this bleach-blonde Canadian was able to climb the ranks of rakugo, then find success with the Japanese storytelling tradition off Broadway. Excerpts from our chat follow.

Origami: How did you first get interested in rakugo?

KS: The work I was doing at the time was based on Aristophanes and ancient Greek theater. While researching that, I found an article written by a scholar that said the Greek comedies and tragedies of 2,500 years ago and Japanese noh and kabuki have all these similarities. That’s what brought me to Japan in the first place. It says something basic about human beings that these two completely different traditions have so much in common.

Anyway, after day three in Japan, thinking I would stay only a couple of months, do some research, and go home, I just got hooked and I stayed. In about year five, when I could speak some Japanese, there was this yakitori restaurant I would go to every day, and the guy who owned the restaurant ― the master or taisho ―said to me, “If you like Japanese culture, I hold a rakugo show once every month or two in my restaurant. We have a tatami room upstairs and we turn it into a little theater. Why don’t you come?” I had never heard of rakugo. What is this thing they call rakugo? At the time, I couldn’t just google it to see if I liked it. Twenty-one years ago, there really wasn’t that kind of information available. You could go to the library, but it would take you a lot longer! So I said, yeah, I’ll come see it, and it blew me away. I thought, this is what I was born to do.

O: I read that the yakitori master told you it was going to be next to impossible to achieve that dream.

KS: For one, there were no foreigners. There had been one a hundred years ago, but there wasn’t at the time. Number two, there is a strict apprenticeship you have to go through. You have to be accepted by a master. I eventually ended up doing the apprenticeship, but he didn’t think I would be that crazy or go that far with it. You have to get a master to take you. What (the restaurant owner) said was actually correct. But he knew I played the accordion, so he said, write some jokes and get a 10-minute routine together with your accordion, because in the rakugo shows they have things called iromono, which is “colored things,” literally, but it means anything besides rakugo that’s on the ticket in a rakugo theater. It could be manzai, which is two-person comedy; it could be mandan, which is standup comedy, and the mandan could be shamisen mandan, accordion mandan; it could be a traditional juggling act called daikagura ― it’s something to allow you to take a break from rakugo storytelling. The reason they call them iromono is because on the poster outside that lists everybody performing that day, they’ll write the iromono in red so that you know it’s not rakugo.

So I created a routine, and he put me in some shows. That’s how I got into the dressing rooms where the rakugo storytellers were preparing for the shows. When I saw them interact, the way they greeted each other – I’m the 15th apprentice to such and such master – the entire atmosphere of it! It was like samurai culture is alive and well in Japanese comedy. It was so traditional, so interesting that I actually go hooked on that even more than the performance. The performance side was incredible, but I really wanted to be part of this world. I wanted to be on the inside. After the show, they all go out to have a drink and talk about rakugo and all kinds of crazy things. The real comedy starts after the show! I got hooked on the world and the people, and I thought, I just have to figure out a way to do this.

O: You finally get accepted by a rakugo-ka to do your apprenticeship. From what I understand, these apprenticeships are a lot of hard work often unrelated to the craft.

KS: That’s exactly it. I went to my master’s house every day for three years, not one day off, did the laundry, the cleaning, folded kimonos, did menial chores. You are with him every waking hour. You can’t go home until he says, “Alright, I don’t need you anymore. See you tomorrow.” That’s your servitude. It’s very, very intense. He gets mad at you every day. The first month, he is really nice, but then he gets sick of you. You kind of think, oh man… You don’t even mind him getting mad at you because he’s getting mad at you. It’s more that he gives you everything; he gives you a name, you get to be with him all day, so you really learn so much more than going to a class at a school or paying money for lessons. You are learning the lifestyle, you are learning everything. In his most private moments, you are there. It’s incredibly valuable. To receive all this from him, and for him to get mad at me because there is still dust on the counter, I think, I can’t even do that right! How much more can I piss this guy off?

The older brother and older sister storytellers (ani-deshi and ane-deshi), as we call them, are all super-nice. They check in once in a while. A couple of them would just love to hear about my most recent mistakes. How are you driving the master crazy this time? They would come just to hear that. They loved it. They laughed so hard! That’s what happens when a Canadian becomes an apprentice!

Because they were laughing, that lightened it at first. At least they’re laughing! I’ve got good material for the future. But they said, look, don’t worry. You’ll get through it. Just try not to do the same thing twice. Don’t quit! They know that anyone doing the three years might quit. They didn’t want that. They were very nice. It was certainly more than endurable.

Also, what you learn by being with someone every waking moment for three years … there’s a reason to do the apprenticeship. There are some people – Japanese and foreigners – who learn some stories, give themselves a name, and say, oh, I’m a rakugo-ka. Technically, they shouldn’t use the word “rakugo-ka” unless they’ve done the apprenticeship and gotten a name from a master and joined one of the rakugo associations, but I can see why they want to do that, because it’s a long apprenticeship. It’s an initiation, plus you observe so many things. Just little details like he might get mad at me for leaving dust on the counter one minute, and then the next minute, he’ll be talking to one of his fans, or a TV producer, or a journalist on the phone or in person and you see the immediate switch in the level of language and interaction. You can’t pay for that.

O: It’s a rich, deep culture that extends back hundreds of years.

KS: Absolutely, and you feel that. A lot of people think you get a name once you finish your apprenticeship, but in rakugo, you get a name right at the beginning, in one month or two monthsa fter starting your apprenticeship. It gives the master enough time to think of what would be a good name for you. My master wrote in his book that it’s his policy to give a name as soon as humanly possible because until you have a name, you don’t really feel like you belong; you don’t really feel like an artist. So you don’t even know one story, you can’t even fold a kimono, it’s been one month, and you already have a name, which is basically a license to call yourself a rakugo storyteller. That’s the order of things.

Katsura is a name that goes back a couple of hundred years. I can trace it. They have storytelling family trees. My master’s name changed after I became his apprentice. He ascended to his master’s name, so now he’s Katsura Bunshi VI, so he’s the sixth person to hold this name.

O: And you took rakugo to off-Broadway. Did your master want you to do that?

KS: That’s a really good question. One thing that’s a little bit ironic is that I was writing musicals. One of my musicals ran in Toronto for 15 months. It was kind of a hit. At that time, I talked to a Broadway producer. He said, your cast is too big for off-Broadway and I’m not going to raise $3 million for a Greek show on Broadway. At the time, I had 13 people in my cast. I could have cut that down. Now I know I could do it with one person! Just tell me the size you want. At the time, I thought that my play was my play and I had to do it that way. I was 25 and didn’t know better. I had my eyes on New York and Broadway and off-Broadway. I thought at some point, I am going to get there.

But here’s the thing. Of course I’d love to go to New York and be a playwright and do all that. But doing rakugo looks even more interesting. When I started, there was not one other foreigner doing it. What an opportunity. So I thought, I’m going to forget my dreams of Broadway, this is where I am going to make my mark. So I literally erased those dreams because I found better dreams – to be a rakugo storyteller. I thought, I’ll go abroad and I’ll demonstrate the art form, but I didn’t think it was going to become a commercial product in the way it has.

When my master named me Sunshine, using the kanji for “three” and “shine,” which was part of his name, he had one eye on me performing abroad and having a name that people would love no matter where I went. He definitely wanted me to spread the art form abroad, and I’ve been able to do it in English and French.

After I finished my apprenticeship, I got invited by Japanese embassies and consulates all over the place. Their mission is to spread Japanese culture, and they’ll pay for flights and a very nice hotel room, no complaints there. But there’s no real payment. I got like 1,000 ($80) yen a show. That’s the standard thing. They don’t take any money at the door.

But people seemed to love it. At first I was adapting it for the American or Canadian audience. But then I realized that the less I adapted, the stricter I am to the original, the more people are cracking up. My master told me I could adapt the stories, do what I need to do. But Americans and Canadians … if we go to a Japanese restaurant, we want the stuff the Japanese eat. Afterwards we may have a California roll, but first, tell me what the Japanese people like. Now more than ever people are looking for authenticity. So when I stopped adapting and did it hardcore (traditional), people were exploding with laughter. I started thinking, could this work?

I did a tour in 2013, and my brother and my best buddy who are in the financial world, said why don’t we do something extra special at the end of the tour in Toronto. They sold a thousand tickets!

I started working on my show the next day, and it took me six years (to get to off-Broadway).

O: You can perform rakugo in Japanese, English, and French?

KS: In Canada we learn French. But I am doing it in Chinese now too. I do a routine about how there are 47 different ways to say “thank you” in Japanese. It was in English, but a person put Chinese subtitles to it and put it up on Weibo, and it got 8 million views and 27,00 comments! For some reason, all these Chinese people were coming to my New York show. I finally asked a Chinese person after the show, Is rakugo popular in China? The guy pointed at me and said, No, you’re popular in China! I thought, I’d never been to China. What are you talking about? We exchanged business cards, and the guy sent me the link. I was like, Holy crap! And I thought if there’s this much interest in rakugo with subtitles, can you imagine if I performed in Chinese? So I’m learning Chinese now.

I use Google translate for one of my stories, and I just try to read it the way the lady on Google translate does. I record it in my studio, put it out there with subtitles, because I’m pretty sure Chinese people don’t understand what I’m saying! I include a little sign that says, I’m still learning Chinese. If you have time, correct my Chinese and I’ll do a better version of this story in a week or two. People give me all sorts of comments outlining where I can improve. I cheat and work with a Chinese friend too, but then when I put out a new version a week later, people flip. Wow. You improved so much in one week! You know crowdfunding? Well, I’m crowd-learning Chinese now.

O: We’re excited for your performance at Town Hall (virtually) on October 20. Just wish it could be in person. I know you’ve performed here before.

KS: Seattle is great. There’s a huge population of people genuinely interested in Japanese culture. I would walk around Seattle in my kimono, and a bunch of white guys would come up to me and say, “Man, that kimono rocks” while they smoked their recently legalized marijuana.

O: Which stories are you going to do?

KS: It’s interesting you say that. We never decide that. It’s kind of like asking a jazz musician a month before a concert, what songs are you going to play? But if I say something now, I’ll have to stick to it, so why don’t I say something. I will do one traditional rakugo story and one story written by my master. That’s how I open my Broadway show.

When everything re-opens, I hope we can find a date where I perform in person in Seattle.

O: You mentioned there was one other Westerner rakugo-ka more than a hundred years ago.

KS: He was Australian and came to Japan when he was about seven. This was in the Meiji Period (1886-1912). His father ran a newspaper in Yokohama. This guy was crazy! He did kabuki, rakugo, hypnosis. He was a very, very eccentric character, but he was accepted in the rakugo world so he was the first non-Japanese rakugo storyteller. His stories still exist. I perform one of his stories. It’s considered traditional rakugo now.

So I was the second officially. And now there’s two more, a Canadian guy and a Swedish guy. The Swedish guy just finished his apprenticeship. That’s why I gotta make a name for myself. They are chasing me!

O: You got a good start.

KS:Yeah, once I got to Broadway, I thought, OK, it’ll take them a while to get here.

Some people say, Sunshine, you are the only person who could have brought this to Broadway. I don’t agree with that. There are Japanese storytellers who do it in English, and they are hilarious. If a producer put them on and did it right, it could have been a show. But what I will say is that I was the only person who had the combination of the knowledge, since I had been studying Broadway as a playwright for 30 years – I knew generally what it would take to get the show on – and I also knew that I could go in debt a million dollars and it would still be worth it. Only 20 percent of Broadway shows return their investment. If you can just make your show last on Broadway, the future is golden for your show. There is no Japanese storyteller who would do that. Most of them have families. They aren’t going to raise three quarters of a million dollars to do it. That’s the perfect storm that allowed me to do a crazy thing like this.

O: You’ve had excellent reviews in New York.

KS: That’s the way the world works. To prepare for Broadway, I went to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, spent tons of money renting a theater, performed twenty shows in a row sometimes for two people in the audience. You do that to give your show a name and get reviews. I never got one good review. When I did get reviews, they were very lukewarm.

I was torn. If I can’t even get one good review at the Edinburgh Fringe and all these people around me are getting five stars, what’s going to happen when we get to New York? If you had come to me in Edinburgh in front of five people, you’d be like, yeah, I don’t think this is going to work on Broadway. You just never know!

Even a Japanese producer told me there’s no precedent for rakugo on Broadway. You should do it standup comedy style and change the noodles from udon to spaghetti, he told me. They were telling me crazy stuff like that!

The whole reason it could work is because I was the first one to bring it to an off-Broadway theater. If I lose all the investors’ money, I thought, I’ll go on an apology tour!

——

Town Hall Seattle and Washin Kai (Friends of Classical Japanese) Present:

Rakugo by Katsura Sunshine

This online live broadcast is free and open to all. But you must register at the link below to gain access.

https://townhallseattle.org/event/katsura-sunshine-livestream/

Tuesday, October 20, 2020

7:00 p.m. PDT

Author profile

- Bruce

- Bruce Rutledge loves books, baseball, and Pacific Northwest beer, He also loves Japan and has dedicated his career to telling more stories about the country through books, magazines, newspapers, TV, radio, and now, on Origami magazine. He works in Seattle's Pike Place Market. Come visit him in his store in the Down Under.

Latest entries

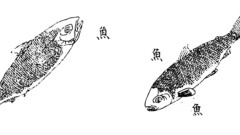

JAPAN2021.04.21KANJI-GATE: Fish Radical

JAPAN2021.04.21KANJI-GATE: Fish Radical WORLD2021.04.20ORIGAMI Vol 17 – Blowfish!

WORLD2021.04.20ORIGAMI Vol 17 – Blowfish! JAPAN2021.04.09Japan’s Fishing Paradise

JAPAN2021.04.09Japan’s Fishing Paradise WORLD2021.04.08Honor Your Fish

WORLD2021.04.08Honor Your Fish