An artistic renewal project at a 600-year-old temple gets a dose of youthful energy

In the heart of Kyoto, on the grounds of a serene Zen temple, a young woman transforms sliding panels, known as fusuma, into vibrant works of art.

Yuki Murabayashi has been working at the temple as a resident artist since 2011. Her life is a mix of morning chores, study, Zen training and lots and lots of painting. In the six years since she began this project, Murabayashi says she has been transformed herself.

“This experience has reshaped my attitude toward the production of my artwork,” she told Origami. “I used to create the artwork based on what I wanted to express. Now, I think about what viewers will look for … Of course, if you just create something that others want, the work will be mediocre. I need to balance between the two.”

Her quiet life on the grounds of this ancient temple has heightened her sense of the world around her. “I became very perceptive of the daily scenery around me,” she said. “The trees show their expressions not only when blooming but when losing their flowers.”

Murabayashi’s perception and artistic vision are transforming the temple one panel at a time.

This young woman’s artistic journey is emblematic of a trend among Japan’s younger generation to reconnect with Japanese culture and traditions. Ever since the tsunami of March 11, 2011, young people have been taking stock of their country and exploring ways to celebrate its best aspects. They’ve shown increased interest in contributing to society, simplifying their lives, and slowing down long enough to notice that trees are also beautiful when they lose their flowers.

In a radically connected and frenetic world, it turns out that the younger generation can learn quite a bit from a temple that has been standing in one place for more than 600 years.

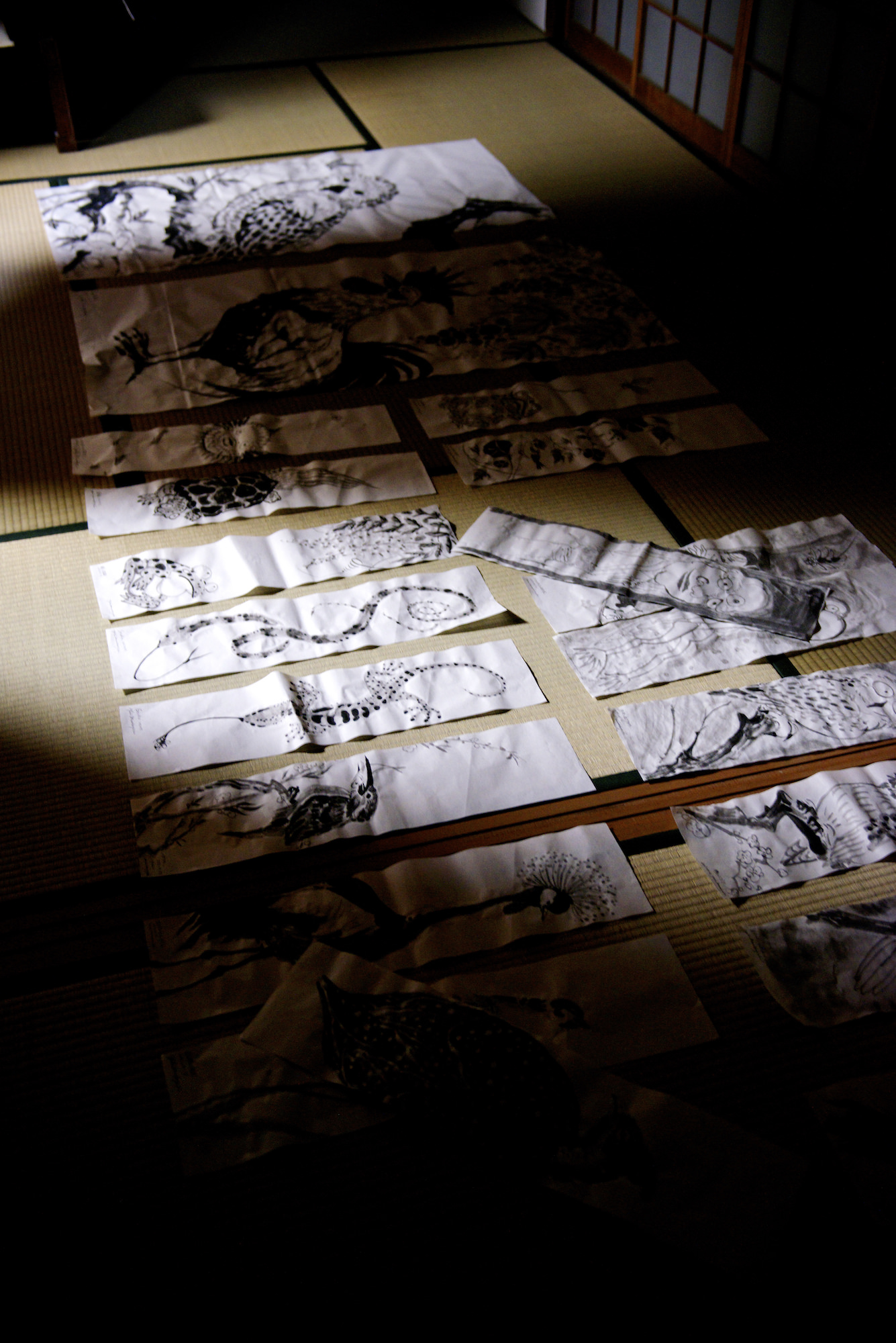

One of the first things Murayabashi learned was not to rush. For the first six months of the project, she practiced black and white painting and Zen. It wasn’t until 2012 that she actually started painting one of the fusuma, in the drawing room.

Fusuma are sliding screens or doors that separate rooms in a traditional Japanese house. The Japanese have painted on them for centuries. The classic fusuma painting is done in sumi-e black ink style. This is the style Murabayashi chose to work in as well.

But how did this young, modern woman end up spending years in an ancient temple painting doors? This is the story of a city and a culture looking to revitalize itself by fusing old and new.

The story starts at Taizo-in, a temple in Kyoto that is steeped in history and culture. A dry landscape garden designed by Motonobu Kano dates back to the 16th century. One of Japan’s oldest ink paintings, a masterpiece by Josetsu, is housed here. Taizo-in was established in 1404 as one of 46 sub-temples in Japan’s largest Zen Buddhist monastery, Myoshinji Temple. It is one of the few Zen sub-temples that are open to the public all year round. People come here to practice Zazen meditation, practice calligraphy, experience the tea ceremony, and dine on shojin ryori, a simple vegetarian cuisine.

Taizo-in was in dire need of some renovation. Parts of the temple had fallen into disrepair, and some of the interior had grown dull over time. The paintings on the fusuma were old and faded.

Taking care of a 600-year-old temple means constant renovation and renewal. For Taizo-in’s Reverend Daiko Matsuyama, repairs and renovations were just part of the job. Yet he felt strongly that the temple needed more than upkeep – it needed to connect in a meaningful way with the younger generation.

Matsuyama represents the third generation of his family to be head priest at Taizo-in. He is a progressive, modern priest, giving a Tedx talk on zen, traveling overseas to promote the religion and Japanese culture, and serving as an ambassador to the Japan National Tourism Agency. The University of Tokyo grad speaks fluent if slightly accented English. He is the kind of modern Japanese who is at home with people of all cultures. In fact, he often leads tours of foreign tourists at Taizo-in interested in zazen meditation, shojin ryori, and other aspects of Japanese culture.

Matsuyama spearheaded the search for an artist who could help Taizo-in paint 64 new fusuma-e. He enlisted the help of the Kyoto University of Art and Design to form a panel of judges who would select an artist to work at Taizo-in. The group interviewed about 30 applicants and settled on Murabayashi, who then promised that she would live in the temple until all 64 fusuma had been painted.

The project was not without controversy. Murabayashi had never done sumi-e style paintings before taking on this job. “I practiced sumi-e a lot. I even painted on the fusuma in the room that I rented as a studio,” she says.

The idea of a young, untrained artist taking on a culturally important project in an ancient temple didn’t sit well with everyone, she recalls. “When the project started, there were people who were against it. Now, I think people have recognized that this project enriches the lives of all the people who are part of it,” she says.

Murabayashi paints in bold strokes, a style that suits her to fusuma-e painting. She also works quickly, whichh is important for someone whose job has expanded to include about 200 fusuma, not just the original 64. Her style shows a confidence that her demur appearance belies. She has a steadfastness about her that is suited to the long-term commitment she has taken on. She lives quietly on the temple grounds, paints, and plans her massive project one sliding door at a time.

“At Taizo-in, I clean the garden and mop the floor in the morning, which is called samu,” she says. “During the day, I usually map out ideas and practice sumi-e. I go to train at a Zen temple in Shizuoka several times a year. During the training, I wake up at 3am and do samu, and then meditate for several hours a day. I have become open to my inner self through zazen meditation.”

Murabayashi has finished fusuma in the drawing room and the main hall, but there is still much to do. While a project of this scope may be daunting to many, Murabayashi takes it in stride. She realizes that she’s leaving a legacy behind. As Reverend Matsuyama points out, the temple is hoping Murabayashi’s fusuma paintings will entertain visitors for the next 400 years.

Location & Contact Information

Taizo-in Zen Buddhist Temple

35, Myoshinji-cho, Hanazono Ukyo-ku, Kyoto 616-8035, Japan