Fish Stories

Some Common Misconceptions about Sushi & Seafood

From Origami Magazine

“Local” and “fresh” have been touchstones among foodies for so long that it seems sacrilegious to suggest that the seafood we eat should be anything else. But sometimes the sashimi we slice and the fillets we grill taste better when the fish is aged and imported. How could a fish caught halfway around the world end up tasting better than one pulled from local waters? We spoke to some of the top chefs in the US to find out.

“The difference between fish caught in the US and fish caught in Japan comes mainly from how they are handled once they are caught,” Chef Daisuke Nakazawa tells us over a recent Zoom call. “By ‘handled,’ I mean how the fish is prepared and delivered to the table. The process is much more detailed in Japan. I don’t think the quality of the fish in the ocean changes that much.”

Nakazawa is head chef and co-owner at Sushi Nakazawa in New York, Washington DC, and most recently, Aspen, Colorado. He also worked under perhaps the world’s most famous sushi chef, Jiro Ono, for more than 11 years at Sukiyabashi Jiro. Nakazawa has an intimate understanding of the marketplaces on both sides of the Pacific.

A big obstacle for US-based sushi chefs, he says, is an outdated American distribution system. “In Japan, when a fish is brought into port, sales are organized by that afternoon and the fish can be consumed that day. That doesn’t happen here! To keep expenses down, the fish is mostly transported by truck, not airplane. When we buy fish locally and age them, the flesh isn’t full of life. They lose their firmness. The fish gets over-extended.”

One way Japan-sourced fish doesn’t get over-extended when shipped overseas is a unique killing method known as Goto-jime or ike-jime. The technique, widely used by fishermen in the waters around Goto Island off the coast of Kyushu, is both more humane to the fish and more apt to pack in the fish’s inherent freshness. The Goto-jime method is a series of steps aimed at controlling the biochemical reaction to the fish. According to the Michelin Guide, a fisherman using the Goto-jime process will do the following in a matter of seconds after hauling in a fresh catch:

-

- First, spike the fish’s brain (located above its eyes) in a process called “closing the fish.” If done right, the fish doesn’t have time to send stress signals to the rest of its body.

- Next, cut the gills and tail. The gills are where a fish’s major blood vessels are.

- Then, run a wire along the upper side of the fish’s spinal cord. This destroys the fish’s nervous system and keeps it from sending out stress signals.

- Finally, let the fish bleed out. If this process is done quickly and correctly, the umami of the fish is maintained while the fishiness that turns off some consumers is eliminated. Plus, the fish is killed quickly, minimizing the trauma.

On a recent visit to Sushi Kashiba in downtown Seattle, Chef Shiro Kashiba was cleaning and preparing some amberjack flown in from the Goto region. “It’s too fresh,” he said with surprise. “It’s full of life. So healthy!” He predicted the fish would reach maximum flavor in three or four days. “We can keep this fish in the restaurant longer,” he added.

Left: Chef Shiro Kashiba of Sushi Kashiba with amberjack from the Goto region

Joseph Geiskopf, a Los Angeles-based chef who once worked at Noma and has spent extensive time in Japan, says a prevalent myth among sushi fans is that fresh is always best. “Most fish is either aged in some sort of way or is handled in some sort of way to process it properly,” he says. “You have squid, octopus, certain things that undergo a process. The general Western mentality is you shouldn’t freeze something, but octopus frozen at a certain time undergoes a tenderness.”

Kenji Yamamoto has been making sushi at his Seattle restaurant Shiki for the last 20 years. He’s seen a huge change in American taste for seafood, but there are still lots of misconceptions. “A customer will ask me if we have fresh salmon,” he says. “I’ll tell them that our salmon is frozen, and they won’t order it. But salmon carry a bacteria, and you need to freeze them for three days. People think as long as it’s fresh, it’s good. That’s not true.”

Shawn Applin, executive chef at Italian restaurant 84 Yesler in Seattle’s Pioneer Square neighborhood, sampled some kanpachi (amberjack) from Goto Island. “The kanpachi is one of the best flavorful fish I have ever eaten. Ever,” he says with emphasis. The Goto-jime process “produces really clean fish. The flavor comes through in the meat.”

Right: Shawn Applin outside 84 Yesler in Seattle’s Pioneer Square

If you live in the Seattle area, you may have a chance to try some of the fish imported from Goto Island because several restaurants were getting large samples from Japan in the middle of February. As of this printing, those restaurants included 84 Yesler, Ascend, Kiku Sushi, Seattle Fish Guys, Shiro’s Sushi, Sushi Kappo Tamura, Sushi Kashiba, and wa’z.

Author profile

- Bruce

- Bruce Rutledge loves books, baseball, and Pacific Northwest beer, He also loves Japan and has dedicated his career to telling more stories about the country through books, magazines, newspapers, TV, radio, and now, on Origami magazine. He works in Seattle's Pike Place Market. Come visit him in his store in the Down Under.

Latest entries

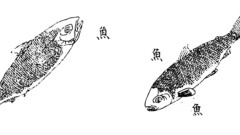

JAPAN2021.04.21KANJI-GATE: Fish Radical

JAPAN2021.04.21KANJI-GATE: Fish Radical WORLD2021.04.20ORIGAMI Vol 17 – Blowfish!

WORLD2021.04.20ORIGAMI Vol 17 – Blowfish! JAPAN2021.04.09Japan’s Fishing Paradise

JAPAN2021.04.09Japan’s Fishing Paradise WORLD2021.04.08Honor Your Fish

WORLD2021.04.08Honor Your Fish